I. EGYPT THE REALM OF THE GODS.

"Spirits or gods that used to share this earth with man as with their friend." — coleridge

Past time is an indefinable perennity. We can nowhere find a place at which to erect a monument to signify that then the earth began existence, or even that human beings then began to live upon it. Indeed, such a thing would be like dating a period of birth for the Supreme Being. Without a creation we would not be able to conceive of a Creator, and without human souls endowed with intelligence it is not possible to imagine that there is the Over-soul.

We need not be abashed at any discovery or demonstration of ancientness for peoples that have dwelt upon the earth. We may not think of this present period of history as being an oasis in the great desert of human existence, or that there was never another period equally prolific of attainment and achievement. Such is only the boast of a sciolist, a vagary as of one's infancy. In our first years of life we are prone to consider everything as existing for our sake, but as we become more mature in intelligence, we learn that we ourselves are only individual elements in the infinite scheme. This Present, our own period of immediate accomplishment, is itself but a moment in the life of ages, a bubble floating on a shoreless ocean. We are not an isolated colony of human beings; there were multitudes in all the centuries that have already passed, and sages, seers and bards flourishing before our historic records were begun. They were our brothers, worthy to be our teachers, recipient of Divine influences, and skilled in knowledge and the arts.

Perhaps a discipline like theirs would make us partakers of the same enlightenment and gifted with similar illumination. What, indeed, if the Canon of Prophecy, sometimes affirmed to have been closed, should be found to be still open, and so the Past and Present to be at one? It may yet be successfully demonstrated that what has been handed down by tradition, and what has been declared by poets and sages respecting an archaic Golden Age was by no means fabulous or untrue.

The delineation is certainly far from seeming improbable. We can read the description which Hesiod has given with a feeling amounting to sentiment that it is a mirroring of fact. "The Immortals made a Golden Race of speaking men," he declares. "They lived," he goes on to say, "they lived as gods upon the earth, void of care and worry, apart from and without toilsome labors and trouble; and there was not a wretched old age impending over them. Always the same in strength of hands and feet, they delighted themselves with a festive life, beyond the reach of all calamities; and when they died it was as though they had been overcome by sleep. They are now good demons moving about the earth, the guardians of mortal men. Theirs is truly a kingly function."

The poet then treats of a Silver Race, which is inferior to the others, growing up for a hundred years as children that are still under the care of their mothers. Their period upon earth he describes as having been comparatively short, but they had honor in later times as divine personages. A Brazen or Copper Race succeeded, flesh-eating and terrible, often engaged in conflict and perishing at the hands of one another. There were also the heroes or half-divine ones, the offspring of gods and human mothers. After them came our present Iron Age, in which mankind are shortlived, irreligious, disloyal to parents, addicted to war and fraudulent procedures, and in innumerable ways evil-minded and unfortunate. As described in the Older Edda: —

Brothers will fight together

And become each other's bane;

Sisters' children their sib shall spoil.

Hard is the world.

Sensual sins grow huge.

There are axe-ages, sword-ages,

Shields cleft in twain;

There are wind-ages, murder-ages,

Ere the world falls dead.

There has truly been much forgotten, even of the times which have been regarded as the period of the infancy of the world. "What we call the history of man," says Dr. Knox, "is a mere delusion, a mere speck when compared with the prehistoric period." (1)

In analogy to this has been the foretime of Egypt. Far back, very far back in this forgotten period of remote ancientness, Egypt had its beginning. No memory, no record, not even a monument has been found that might afford a solid foundation for anything beyond conjecture. Nevertheless, queer as it may sound, A. M. Sayce, the distinguished Orientalist, declares that although it be historically the oldest of countries, it is geologically the youngest.

We may, indeed, infer as much from Grecian tradition. There was a period when there was the populous country of Lyktonia, connecting Greece with Asia, while to the North there was a vast inland sea, including within its limits the Euxine, Kaspian and Azoff, with a large region beyond in every direction. (2) Thessaly was then a lake enclosed by mountains. After this came volcanic eruptions and seismic convulsions of such violence as to change the configuration of the whole region. It was related in Grecian story that these volcanic fires were still burning at the time of the Argonautic expedition in quest of the Golden Fleece. The Euxine forced an outlet southward to the Mediterranean, overwhelming Lyktonia, henceforth the Archipelago, and deluging all Greece. The mountains of Thessaly were also rent apart, and the waters of the lake were drained into the new-made Ægaean Sea. Europe was thus divided from Asia Minor, and the steppes or prairies at the North, which had before been under water, now became dry land. Not only was the face of the world transformed physically, but a change also followed in culture, art and social tendencies.

Egypt was necessarily affected by these transformations. The Levant, once an inland lake, was swelled beyond its former dimensions by the immense mass of water now coming down from the Black Sea. The Libyan Desert was covered, except the oases, which remained as islands above the surface, and lower Egypt was submerged. Eventually, a way was made for the sea to the other basins of the Mediterranean, and an outlet into the Atlantic soon opened at the Pillars of Hercules. The dark-skinned Iberians of Spain were thus separated from their African congeners, while Greece, Egypt and Libya again appeared above the water.

Since that time, the Nile has continued without ceasing for centuries, and even thousands of years to bring down from the South an annual contribution of soil, thus building anew the engulfed territory (3) and maintaining in its remarkable fertility that most famous oasis of the Dark Continent which has furnished so much history, art, physical science and religious dogma to the world. (4)

But whence the inhabitants originally came is one of the curious problems of ethnography. The Bible distinctly represents them as akin to the Kushites or Ethiopians, who peopled the region of Southern Asia from the Indus westward clear to the Atlantic in Africa. Diodoros, the Sicilian historiographer, cites a confirmatory declaration of the Ethiopians of Nubia that they were a colony led from that country into Egypt by the god Osiris. Affinities of race and language have been pointed out between the Fellah peasantry, Barabazas (Berbers) of Nubia, and the Fellata peoples of Senegambia. There were, however, distinct types of the population; and the late Samuel George Morton regarded the primitive inhabitants as having come into existence by themselves, a distinct human race, indigenous or aboriginal, in the valley of the Nile.

Brasseur de Bourbourg, however, would intimate that they might have been colonists from the country of Atlantis, which the Egyptian Priest, Sonkhi, described to Solon as having sent forth invaders, nine thousand years before, into Libya, Egypt and Archaic Greece. Diodoros, however, relates a story of the Amazons, former inhabitants of Hesperia, in the Lake Tritonis, near the ocean. They vanquished the people of Atlantis and then set out under their Queen, Myrina, to conquer other countries. Horos then had the dominion of Egypt, and entertained them as friends and allies. After this, it is said that they pursued their march and overran Arabia, Syria, Asia Minor and Thrace. Conflicting accounts, however, render their identification difficult. One writer affirms that their country was called Assyria, and earlier accounts certainly recognize an Assyrian dominion in Asia Minor at a period anterior to historic records. They are said to have founded Ephesus, Smyrna, Kyma, Paphos, Sinope and other cities. Plato states that they invaded Attica under the command of Eumolpos, who is reputed to have established the Eleusinian Mysteries. Like all ancient conquerors, they are represented as the missionaries of a religious propagandism, instituting the worship of the Ephesian Goddess-Mother, Artemis Polymastos, the counterpart of the Indian Bhavani, and introducing the pannychis or watch-night and processions, which were characteristic of the worship of Bacchus, the Syrian Goddess, and the Great Mother. (5)

It is evident, however, that in ancient time, as at the present, the population of Egypt consisted of a variety of races. If there existed a prehistoric people to which we might attribute the relics of the "Stone Age," which have been brought up from a depth of many feet beneath the surface of the ground, (6) we have little evidence in relation to it.

The peasant and laboring population were not negroes, despite the assertion of Herodotos; and, indeed, when negroes are depicted on the monuments, they are represented as captives or in a servile condition. (7)

The laboring class was obviously of Arabian origin, (8) but the figures which are most common on the monuments of Upper Egypt, have a close family resemblance to the Barabara inhabitants of Nubia, but as we approach the Delta at the North the prominent faces are Caucasian, like the modern Kopts, indicating the presence there of a different type of population. (9)

The vast antiquity of Egypt is beyond question. The time required for the annual inundations of the Nile to accumulate the earth to the present depth at Memphis must have exceeded eleven thousand years. Herodotos remarks that "No Egyptian (10) omits taking account of extraordinary or striking events." Yet, however, archaic any record may be that has been found, it is quite certain to contain some allusion relating to ancient men of earlier periods. The priest who discoursed with Solon spoke of records at Sais that were eight thousand years old, and Plato mentions paintings and sculptures made in Egypt ten thousand years before. Diogenes, the Laertian, who wrote sixteen hundred years ago, declared that the Egyptians possessed records of observations made of 373 eclipses of the sun and 832 of the moon. These must have been total or nearly so, as others were not noted. This indicates an equal or greater ancientness. The traditions of the period prior to the "First Empire" as preserved by Manetho (11), seemed to indicate a duration of nearly twenty-five thousand years. It is common to designate this period as "mythic," it not having been demonstrated by modern research or evidence that is currently accepted. Perhaps this is right, but it may be wiser to leave the question open. There are extremes in such matters which it is well to avoid. Some following the concept of omne ignotum pro magnifico, consider that what they fail to comprehend must be very grand; and others, in the pride of conceit, are equally superficial, and set down everything as fabulous, fictitious or not worthy of attention that is beyond their range of view.

The government of prehistoric Egypt, so far as it has been traced, was theocratic, a rule of royal priests. (12) The Egyptians were the first, Herodotos declares, to introduce solemn assemblies, processions and litanies to the gods. We are safe, however, in assigning these elaborate observances to that later period in the history of the country when external rites were conceived to have a greater importance. "In the beginning it was not so." It is necessary for us, however, to bear in mind that in those remote times, no pursuit that exalted humanity was esteemed as "profane" or secular. But it was included within the domain of worship. The ministers of religion were the literary men and teachers of knowledge, and united the functions of worship and instruction.

In the very early period prior to the "Empire" the priests of Amun told the historian, Hekataeos, (13) that "Egypt had gods for its rulers, who dwelt upon the earth with mankind, one of them being supreme above the rest."

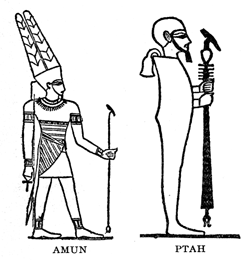

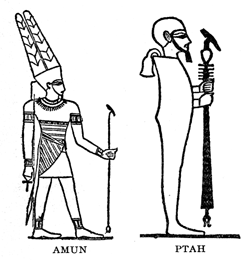

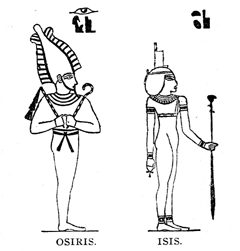

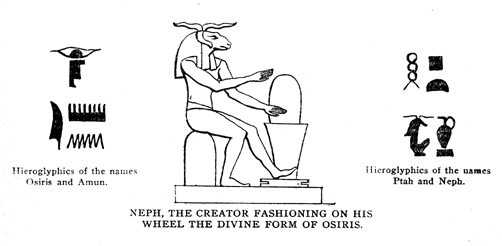

The first of these, in the Northern records, was Ptah (14) (or Hephaistos), the Divine fire, the Demiurgos or Former of the Universe and tutelary god of Memphis. He was succeeded by Ra, or Phra, the Sun-god (15) who was worshipped at On or Heliopolis. In regard to the third there appears a discrepancy among writers. He was represented to have been Neph (Kneph) or Num (Khnoum) the Chrest, Agathodaemon, or Good Divinity. (16) Later writers however generally agree that the third was Shu or Sos, the first-born son of Ra and Hathor, the god of light and of the cosmic or electric energy.

In the Turin Papyrus, which was compiled in the time of the Ramesids, we find these three names erased. The seat of government and national religion had been changed to Thebes, and the tradition was modified accordingly, as follows: Amun-Ra, the hidden or unknown, the Hyk or king of gods. He was succeeded by his son Manthu (or Ares), the "protector of Egypt." Next was Shu (or Herakles), the son of Ra, and god of light and cosmic energy. (17)

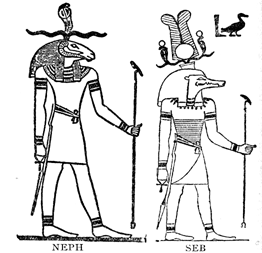

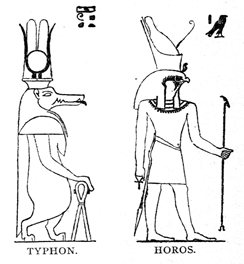

The next in the category was Seb (or Kronos), in many respects the counterpart of the Indian Siva. He was a personification of the Earth, and of Time, without beginning or end. He was succeeded by Uasa or Isis and Uasar or Osiris, and they by Seth or Typhon, their brother, the "beloved of the World." The next was Hor or Horos, the son of Isis and Osiris, who "ruled over Egypt as its last god-king." (18)

There were traditions also of the Hemi-thei, or Lesser Gods, the Hor-shesu, or followers of Horos and Heroes — "sacred princes of the primeval times, who were said to have reigned several thousand years."

Mr. Sayce declares emphatically that there is no evidence to show that Egyptian civilization was introduced from abroad; and he adds that "the high perfection it had reached before the date of the earliest monuments with which we are acquainted implies unnumbered ages of previous development."

These representations, we may therefore fairly presume to cover the period of the Golden and Silver Ages of Archaic Egypt. Doubtless, behind the mythologic relations, which have been shaped at a later era and transmitted to later times, there was a sublime and recondite philosophy, furnishing a key to the whole. The array of divinities that thronged the Egyptian Pantheon, it may be borne in mind, only represented different attributes in the God-head.

"They were only manifestations of the one Being in his various capacities," as M. Pierrot has aptly remarked. We find accordingly the several divinities more or less compounded together, are described as being endowed with similar powers and qualities, exercising each other's functions, and sometimes even merging into one another as beings of one substance. Indeed, Egyptians generally regarded them, however named in the different precincts, as only designations of the Supreme One, whom they thus represented and symbolized. In the hymns employed in their worship we find one God accordingly celebrated as the Only Divine, Eternal, Infinite, and abounding in goodness and mercy, as these selections abundantly show.

"God is One and Alone, and there is none other with him:

God is the One, the One who has made all things:

God is a Spirit, a hidden Spirit, the Spirit of Spirits,

The Great Spirit of Egypt, the Divine Spirit.""Unknown is his name in Heaven,

He does not manifest his forms!

Vain are all representations of him.""He is One only, alone without equal,

Dwelling alone in the holiest of holies.""He hath neither ministrants nor offerings:

He is not adored in sanctuaries,

His abode is not known.

No shrine is found with painted figures,

There is no building that can contain him!""God is life and man lives through him alone:

He blows the breath of life into their nostrils.""He protects the weak against the strong;

God knows those who know Him;

He rewards those who serve Him,

And protects those who follow Him."

The moral and social condition of the people of Egypt at that earlier period, we may well believe corresponded with the divine character imputed to the government. We may presume them to have been civilized in the genuine sense of the term, (19) living in social relations of amity with one another, and so fulfilling the law of charity as set forth by the apostle. They certainly were not warlike, but always disposed to the arts of peace, even into the historic period. Indeed, they were celebrated as the "blameless Ethiopians." In fact, we have no evidence except that of inference and conjecture, that the prehistoric inhabitants of Egypt were ever barbarous. We may not unreasonably entertain the belief that they were gifted with purer instincts than are now manifested, which eventually suggested to them and impelled to vast achievements.

Savages would necessarily exist for periods beyond computation before they would attempt to write. A race barely transcending apehood would need, if it could possibly dream of such a thing, to establish its articulate sounds conventionally into language to signify specific objects of thought; and after this, distinct characters must be agreed upon to denote each of those sounds. Only mind, capable and receptive of higher inspiration, can effect so much. Immense periods of time must likewise elapse before the progeny of such an enigmatic race could write anaglyphies, (20) and attain that wonderful skill which is attested by the Egyptian monuments yet standing on the banks of the river Nile.

May we not, then, feel ourselves safe in believing that human beings began their career in the earth with that perfect refinement which would seek its appropriate manifestation in the splendid formations of Art? That not long ages of discipline schooled the men of that time, but that the divine instincts implanted in them enabled them to exhibit their exquisite skill in the arts? That what was affirmed by poets and sages of a primeval Golden Age was not all fabulous and untrue?

"We must believe," says Dr. C.H.S. Davis, "that when the Egyptians first came to Egypt, they came, not as barbarians, but in possession of all the knowledge and artistic skill of that long and antediluvian age of which their immediate successors were the survivors." The author here refers to the inhabitants who are signified generally in historic and philosophic works, and not to the earlier population.

The social life of the Egyptians in that far-remote period appears to have been characterized by a charming simplicity, warm family affection, deep religious feeling and great refinement. They were polite, hospitable, and generous even to profusion. Their children were carefully trained to veneration of the gods and respect for the elderly, and the equality of the two sexes was fully recognized. There was no gynaecasum in which women were shut away from view. Both father and mother were enrolled together in the genealogies, and sisters ranked with their brothers in the family. In every temple the Godhead was contemplated as three-fold the Father, Mother and their Divine Son. In this category, the Mother was chief. Queen Isis was supreme in all worship. In the family in those earlier times the children were reckoned as belonging to the wife. Women were supreme in every household. They shared in the festive entertainments, they ministered at religious rites and participated in government and affairs of State. They attended the markets and transacted business of every kind, while the men also sat at the loom at home, plied the shuttle and followed various sedentary pursuits. (21) Diodoros actually affirmed, that in the later periods the husband swore obedience to the wife in the marriage contract.

Young men meeting older persons would step courteously aside, (22) and if an elderly individual came into their company they all rose up and bowed reverentially. (23)

Learning appears to have been very generally disseminated, and in historic times there was an extensive literature. Every temple was a "School of the Prophets." The Egyptians are always described as being very scrupulous in keeping accounts and they carefully recorded everything that was produced or expended. They had their diaries, and made memorandum of all matters of importance. They were skilful in the liberal arts from remote antiquity and it is shown from their paintings that very many things which we enjoy as household conveniences incident to our advanced civilization they also possessed. Mirrors, carpets, sofas, ottomans, chairs, tables, jewelry and other ornamental articles, too many to enumerate, were common in their households. The children had their dolls, toys and other playthings. Men and women performed with various instruments of music as pipes, flutes, drums, cymbals, guitars, tambourines. Even the poor, in the exuberant fertility of the country were able to have their diversions and entertainments.

The fondness for domestic animals and household pets was universal. These seemed to have been regarded as sacred, and at their death were embalmed and deposited in the various sanctuaries. The dogs were companions in their sports; the cats, unlike their less fortunate relatives of our time, were skilful in fishing and plunged boldly into the river in quest of the prey. They were privileged in every house and their death was mourned as a calamity. The ichneumon, the hawk, the shrew-mouse and the ibis shared in this veneration and were regarded as benefactors.

At their banquets, the guests, men and women alike, sat in chairs or upon the ground, but did not recline as in other countries. They were crowned with garlands in honor of the divinity who was regarded as master of the feast and the discourse was of a cheerful and entertaining character. If it was philosophic it nevertheless did not seem so; yet it might compare well with the symposiac talks of Plato, Plutarch and Xenophon. Dancers and flutists were often present to add to the pleasure of those sitting at the tables.

The Egyptians were always passionately fond of games and sports. Wrestling was a favorite exercise. So, likewise, was the tossing of bags into the air that had been filled with sand, as well as other trials of strength. Contests in rowing were very common. They had also games of ball, some of them of a very complex character and requiring great dexterity. Dice was regarded as worthy of gods. The game of draughts or "checkers" was a favorite in all grades of society. It was said to have been invented by the god Thoth.

Indeed, the Egyptians never lost sight of the divine agency, even in sports and social occasions. They were religious everywhere. Even inanimate objects were regarded as pervaded by a sacred aura. It was esteemed a sacrilege to pollute the waters of the Nile or of any flowing current of water. Every action was a prayer, and when uprightly performed it was regarded as bringing the individual into communion with divinity and participation of the gods. In life they were earnest, and when they died an inquest was held upon them before they were admitted to an honorable recognition with the worthy dead.

Whether funeral rites were performed with elaborateness peculiar to the later centuries is very improbable. The characteristic of the prehistoric times was a chaste simplicity. But death was not considered as an extinguishing of life. They doubtless had their beliefs and notions in regard to the soul, and its career in the invisible region. It seems to have been held that it hovered about the body during its disintegration, and hence came the practice of making offerings and libations to render its condition more tolerable. But they also believed that when the process of its purification was completed, when it was free from evil and the taints of earth it left this region for the empyreal home. In short their faith and life were as the poet described:

"To scatter joy through the whole surrounding world, To share men's griefs: Such is the worship best and good Of God, the Universal Soul."

FOOTNOTES:

1. This is exquisitely illustrated in the following fragment by the Moslem writer, Mohammed Kaswini (Anthropological Review, Vol. I, page 263):

"In passing one day by a very ancient and extremely populous city, I asked one of the inhabitants: 'Who founded this city?' He replied to me: 'I do not know; and our ancestors knew no more than we about this matter.'

"Five hundred years afterward, passing by the same place, I could not perceive a trace of the spot when was the city destroyed. He answered city. I inquired of one of the peasants about me: 'What an odd question you put to me! This country has never been otherwise than as you see it now.'

"I returned thither after another five hundred years, and I found in place of the country that I had seen, a sea. I now asked of the fishermen how long it was since their country became a sea. They replied that 'a person like me ought to know that it had always been a sea.'

"I returned again after five hundred years. The sea had disappeared, and it was now dry land. No one knew what had become of the sea, or that such a thing had ever existed.

"Finally I returned again once more after another five hundred years, and I again found a flourishing city. The people told me the origin of their city was lost in the night of time."

2. Some think that the Baltic Sea also extended until it formed a communication with this body of water. This would render plausible the story that Ulysses or Odysseus sailed from Troy by the ocean around Europe and returned home by the Mediterranean. (return to text)

3. According to the statement of Herodotos, all Egypt at the time of Menes except the Thebaic country at the south, was a marsh, and none of the land in the Delta or Faium below Lake Moeris was visible. This point was at a distance from the Mediterranean, which required a voyage of seven days up the River Nile to reach it. (return to text)

4. This country is called Migraim in the Hebrew text of the Bible, from Mazr, the fortified country; also the "Land of Ham" or Khemi, the black land. The Greek name Aiguptos, which was chiefly applied to Northern Egypt alone, has been plausibly derived from the Sanskrit Agupta, the fortified; while others, remembering the Sacred Bird of old mythologies, render it the land of the eagle (or vulture). It can be formed from aia or gaia, a country, and Kopt or Kopht, or the covered or inundated. Brugsch Bey suggests a derivation from Ha-ke-Ptah, the sacerdotal name of Memphis. (return to text)

5. Perhaps this may suggest the key to these legends. The name "Amazon" appears to have been formed from ama, signifying mother, and azon or worshiper. The Amazons, whoever they were, and whatever their origin, were evidently the introducers of the worship of "Nature," the mother or material principle, as the paramount power in creation and procreation. This was signified in the occult rights imputed to them, and by the story of their reception in Egypt, where Isis as mother of Horos was venerated as the all and parent of all. The tradition, almost historic, that they were women, probably took its rise from the presence of women at their rites, participating on equal terms with men; and their fabled antipathy to the male sex may have been a notion having its inception in the custom of human sacrifices. One of their designations, Oior-pata, or man-slayers, suggests as much. The worship of Molokh, Kronos, Poseidon, the Syrian goddess, and the Theban Bacchus, were so characterized, and the mythic exploits of Theseus and Herakles, may be explained as denoting its abrogation. It was represented that the Amazons after their return to Africa were exterminated by Herakles, and likewise that their country was swept away by the Atlantic Ocean. (return to text)

6. Shafts sunk into the earth near the colossal statue of Rameses II at Memphis brought up a fragment of pottery thirty-nine feet under ground. (return to text)

7. Some Egyptian customs, like circumcision, veneration of animals, etc., appear, however, to have been adopted from the negro races. (return to text)

8. In the Book of Exodus, chapter xii, 38, it is stated that when the Israelites left Egypt an "Arab multitude" (arab rab), went also with them. (return to text)

9. The skulls of the latter were brachycephalic; those of Southern Egypt, dolichocephalic. (return to text)

10. It should be borne in mind that the term "Egyptian" when used by different writers, very generally means a person of superior rank, generally a priest, nobleman, or a person educated at a temple, but hardly one of the Fellah commonalty. (return to text)

11. Manethoth, Mai-en-Thoth (Thothma), i.e., given by Thoth, the god of learning and sacred knowledge. (return to text)

12. In Greek, the Egyptian priests are often called basileis, as denoting kingly rank or king-initiates. In the times of sacerdotal rule the priests were styled kings. (return to text)

13. He is quoted without acknowledgment by Herodotus, who never visited Upper Egypt. (return to text)

14. Oriental words are rendered into modern forms of spelling, largely by the judgment or caprice of individuals. Vowels are most uncertain of all. (return to text)

15. The "time of the god Ra" was always mentioned in subsequent centuries, as the happy period, the golden age. (return to text)

16. This god was the personification of the Divine Spirit moving over the primal matter and permeating it, thus rendering it instinct with life. The names Neph and Num (or Pnum with the article prefixed) exhibit a striking similarity to their equivalents, nephesh (soul) in Hebrew and pneuma (breath, wind, spirit) in Greek. The later Gnostic form, Khnoubis may be imagined to be a compound of Nu, the spirit, and Bai, the soul to denote the entire individuality. (return to text)

17. In the later philosophy, the two would seem to have been reconciled. The Supreme Being was set forth as the Monad or Sole One; and then as the Demiurgus or Creator. Iamblichos has explained it accordingly: "The Demiurgic Mind, the Over-Lord of Truth and Wisdom is called Araon, when coming down to the sphere of the genesis of all creation, and bringing to light the invisible potency of hidden things; and Phtha, when establishing all things undeceptively and skilfully with Truth." (return to text)

18. The drama of the Secret Rites, which represents these divinities under a different character was produced in the latter dynasties. Till the Ramesid era, Seth was regarded as identical with the Baal of Syria, and as the benefactor of mankind. (return to text)

19. Professor Francis W. Newman derives this term from the Keltic word kyf or kiv, signifying together. Its derivatives in Latin and English may be defined accordingly. Civis or citizen thus denotes a person living in social relations, and by civility is meant the courteous manners of neighborly intercourse as distinguished from the rudeness and brusque speech characteristic of brute selfishness and savagery. Civilisation, then, is the social mode of living, the art of living in society fraternally, as opposed to that opposite condition of the savage in which "his hand is against every man, and every man's hand against him." (return to text)

20. "Egyptian Book of the Dead," page 40. (return to text)

21. Herodotos II, 35. (return to text)

22. "The young men saw me and made way for me." — Job, xxix, 8, Wemyss' translation. (return to text)

23. "Thou shalt rise up before the hoary head, and honor the face of the old man, and fear thy God." — Leviticus, xix, 32. (return to text)