IN THE PRESENCE OF THOTH, SCRIBE AND RECORDER:

The two illustrations which accompany these notes are really murals epitomized. They came from no temple-walls, however, but from one of the many papyri thus far discovered containing the remarkable text known as the "Book of the Dead" — so called, that is, for the title Pert-em-Hru, correctly translated, means The Book of the Coming Forth into Light.

Supported by an explanatory text in the sacred hieroglyphic, the Papyrus of Ani describes the soul's after-death journey through the invisible worlds of test and trial until, these passed, it becomes "one with Osiris."

Copies of this "book" were customarily laid upon the breast of the mummy or within the mummy-wrappings, that the deceased might know what to expect on this path and make no misstep. When this or a similar papyrus came to light, the story goes, a native workman exclaimed, "Oh, the book of the dead man! The book of the dead!" Hence the name. Now let us examine this mysterious "book," so reverently limned no one knows how long ago.

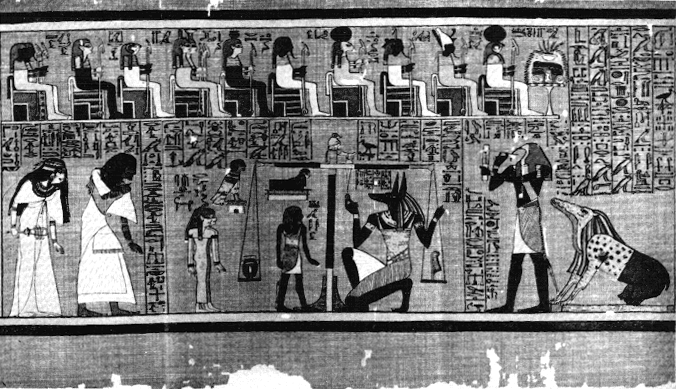

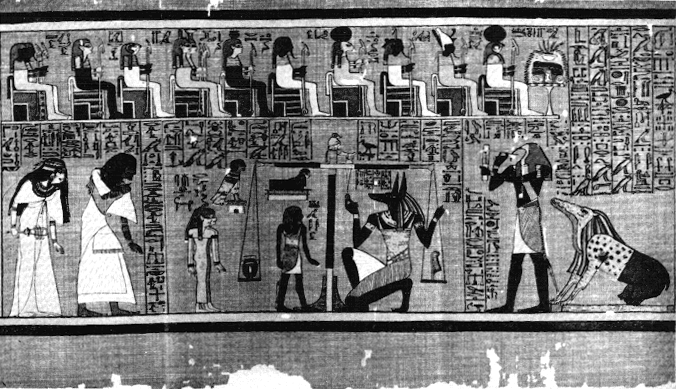

The first picture, a section only, portrays the "weighing of the heart," for Weigh me in an even balance was the prayer sent up in ancient days to Osiris-Ra, Osiris the Sun-God, the Supreme, the object of both gratitude and devotion, "the God who died."

In the center stands the Balance or Scales, an ageless symbol. Anubis, a huge figure with the jackal-head (symbol of terror, darkness, and trial) kneels with his hand upon the pointer, to keep it exactly plumb. Opposite Anubis stands Horus, a "Son of the Sun," or Initiate, the son of Isis and Osiris. He stands, a slight, almost boyish figure, watching to note the result. Behind him stand the goddesses attendant upon Shai, Goddess of Justice. Shai, note, stands protectively behind Ani, who with bowed head also watches the "weighing of the heart," his own.

Above them sit twelve of the Forty-two Assessors or Judges (the picture, bear in mind, is but a section) who, like Shai, are connected with what the Hindu would call "Karman."

At the right of the great Balance stands Thoth of the ibis-head, Recorder and Scribe of the Gods. Tablet and stylus in hand, he records the questions asked of Ani, and the answers or "confession" made — Ani, whose whole life is being bared.

Just behind Thoth is Aman, a grotesque, composite creature, ever on hand at such trials to seize and devour the unfortunate whose heart is so weighted with cruelty and sin that it pulls the scale-pan downwards. For it is the heart, not mind or body or money, that is being weighed, and not in chambers but in open court, against the symbolic feather: Truth.

But who was Ani? Keeper of the Sacred Vessels and the Treasure of the Gods — that is all we know of the outward man. But about the earnest honest soul of him, we know much more, thanks to Thoth and his patient chronicle. Quoting from the record:

I have not done evil in the place of good.

I have not consorted with worthless men.

I have not put my name forward to obtain honors.

I have not domineered over slaves.

I have caused no man to suffer.

I have allowed no man to go hungry.

I have made no man weep. No man have I slain.

I have not stolen the cakes of the Gods.

I have not cheated in the measuring of grain.

I have not encroached upon the fields of other men.

I have not taken away milk from babes.

I have not driven cattle away from the property of the Gods.

I have not extinguished a flame which ought to burn. . . .

This is a portion only of the "Negative Confession," too long to be quoted in full. It is followed by a second "Confession" before the Forty-two Assessors (each one of whom Ani must address by name) in an examination even more searching, for the "Forty-two" are specialists in the gentle task of uncovering the faults or crimes they must condemn. This ordeal ends with the following words, Ani speaking:

. . . Behold me as I am. . . . I live on truth; I feed on truth.

I have given bread to the hungry man, water to the thirsty, clothing to the naked, and a boat to him who has need of one.

Be ye, then, my deliverers and protectors, and accuse me not of evil when I stand before the Great God. . . . Let it be said to me by those who shall behold me: Come unto peace! Come unto peace!

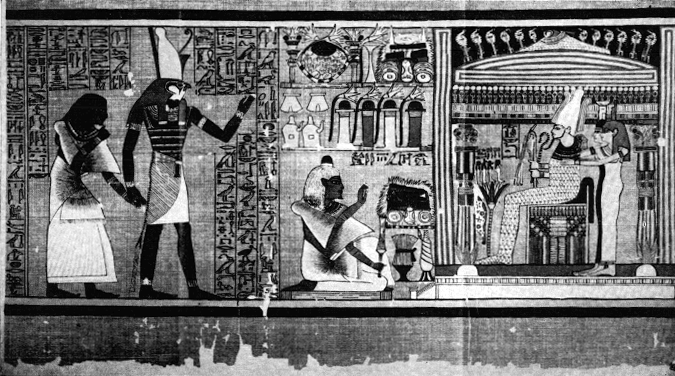

The second illustration, a section also, has three quite separate divisions. In the first (at left) Horus, tall and impressive now, and wearing the double crown, enters leading Ani by the hand. For Ani has passed triumphantly the dread tests of the Assessors and the trials which came after, and is now on his way to Osiris.

The center panel shows us Ani in a sitting-kneeling posture before an altar beneath which is the symbolic sheaf of wheat. The sowing and reaping that governed his life on earth is over. Thus the sheaf, significantly, is raised above the floor to rest upon a cup or chalice. Ani's hair, formerly dark, is now white, but as to what this signifies most authorities will not hazard a guess. Yet the Egyptians of the Divine Dynasties were not the ones to act without a reason in the matter of even slight details in a subject of paramount importance. Each had its meaning, and rather than leave a careless hiatus, let it symbolize the purified soul, mature in years and judgment as Ani must have been; and since the acceptance of his Confession in that grim test by the Assessors, inwardly "white as snow."

Beyond the altar, on a smaller scale yet oddly enough not belittled by it, sits Osiris, canopied and enthroned. In his hands are the shepherd's crook and flail, ancient symbols, not alone in Egypt, of divine guidance and protection, and of justice backed by might. Behind him stand the heavenly or divine Isis and her sister Hathor, the earthly Isis of external Nature. Almost concealed is the latter, as both with outstretched arms support Osiris — in a silence that as the pages of this "book" are turned one cannot but deeply feel — the "divine silence" of Hermes, Thrice the Master.

Ani is now Osirified, "one with Osiris." Darkness and dread are left behind, and unhindered he now may pass to the peace he worked for and won: the "coming forth into Light." Or is there still risk? Yes, for no man in the net and stain of Earth could be entirely sinless, wholly pure. And why, among so many Gods should he be guided only to Osiris? Because justice alone is not enough; there must be mercy also. And Osiris, unlike so many Gods, came down to Earth out of pity and lived there, suffering too. He conquered illusion as mankind must do, while ruling as an earthly king in that still unexplored archaic day when Divine Dynasties were divine, not names. Who then so understanding as Osiris, so wisely merciful?

A mystery? Not at all, as every student of Theosophy must know well. Osiris was in short an Avatara, a rare and special being who out of pity at critical times in human affairs leaves his celestial home to live on earth; through an earthly body to endure the utmost in human pain, and at last to die as men die. But only to rise again. It is a sacrifice, but it is not unique. Recall the words of the Avatara Krishna:

I produce myself among creatures, O son of Bharata, whenever there is a decline of virtue and an insurrection of vice and injustice in the world; and thus I incarnate from age to age for the preservation of the just, the destruction of the wicked, and the establishment of righteousness.

This is why Osiris was the "Great God." This is why he had no nobler title in the torn hearts of those who suffer than these four narrow words: "the God who died."

Two little paintings on papyrus. How much that is profound hides in them!

In the Judgment Hall of Osiris — The weighing of the heart.

From the Papyrus of Ani — The Egyptian "Book of the Dead"

Final Scene in the Judgment Hall of Osiris — Horus Conducting Ani to Osiris

From the Papyrus of Ani — The Egyptian "Book of the Dead"