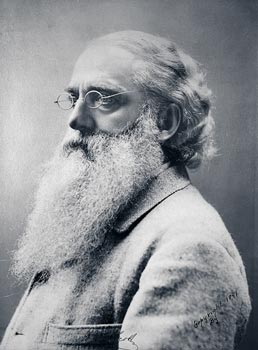

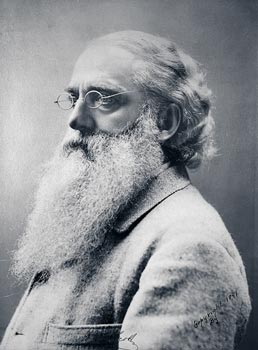

From the age of 42 the President-Founder of the Theosophical Society, Colonel H. S. Olcott, dedicated his energies to fraternal understanding and the search for truth. For him, theosophy was not a new creed with its own set of beliefs: as he explained, “we are not preaching a new religion, or founding a new sect, or a new school of philosophy or occult science.” He encouraged one and all to seek truth in whatever of its religious, scientific, philosophic, mystical, ethical, and practical expressions appealed to them. Olcott referred to theosophists as “original searchers after spiritual knowledge” who obtained their knowledge through “intuition and contemplation” and a “theosophic process of self-illumination.” Through scientific investigation of nature’s physical, psychological, and spiritual aspects the dedicated seeker could discover its laws and secrets. But only by living an altruistic life could a person successfully explore these hidden sides of nature and mankind.

Olcott led an active life before becoming involved with theosophy. In his twenties he pioneered modern methods of teaching agriculture in the U.S. During the Civil War he investigated fraud, corruption, and graft, first in the Army’s New York Mustering and Disbursement Office, and then at the Navy Yards in Washington DC. When Lincoln was assassinated he was on the three-man committee that investigated the murder. After the war he became a successful lawyer, and in the 1870s had the leisure to renew his interest in psychological and spiritualistic research. Over the years he had written for newspapers, and in 1874 obtained an assignment from a New York paper to investigate phenomena taking place at the Eddy farmhouse in Vermont. There he met Helena Blavatsky, and they quickly became friends and associates. In time Blavatsky’s teacher became his guru also. When the Theosophical Society was founded in New York City in 1875, he was elected President, a post he held until his death. In the early years of the Society he supported the organization financially and served as its main public spokesman and lecturer.

In the 19th century non-Christian religions were poorly understood, denigrated, or suppressed by colonial Europeans, and consequently were losing prestige in their native lands. After moving to India in 1879, Olcott and Blavatsky worked to revive Oriental spiritual traditions, at the same time seeking to disseminate Asian philosophy in the West through encouraging accurate translations of texts by native scholars, to whom they also offered a forum in The Theosophist.

Buddhism was the other great love of Olcott’s life. Becoming a Buddhist in 1880, he worked to strengthen that faith for the rest of his life. His activities included aiding Ceylonese Buddhists to establish schools and reduce discrimination against them; writing a Buddhist Catechism; and later working with Buddhists of many different schools to promote mutual amity and reach points of general agreement so they could present a united front to the West.

Olcott continued to travel and lecture until late 1906, when he fell and injured his leg on shipboard. His interests in religious harmony and understanding remained great, and in his brief farewell message of February 2, 1907, he charged theosophists, “In memory of me,” to “carry on the grand work of proclaiming and living the Brotherhood of Religions”; and expressed the wish “to impress on all men on earth that ‘there is no religion higher than Truth,’ and that in the Brotherhood of Religions lies the peace and progress of humanity.”

(From Sunrise magazine, Summer 2007; copyright © 2007 Theosophical University Press)

It is time for a change and, after a continuous run of 56 years, Sunrise will cease publication with the Fall 2007 issue. More details will accompany the last issue.