VII. — TRISTAN AND ISOLDE.

(Continued.)

It would seem that women are more largely swayed by destiny than ourselves. . . They are still nearer to God, and yield themselves with less reserve to the pure workings of the mystery. . . They lead us close to the gates of our being. . . Do I not know that the most beautiful of thoughts dare not raise their heads when the mysteries confront them? It is we who do not understand, for that we never rise above the earth-level of our intellect. . . She will never cross the threshold of that gate; and she awaits us within, where are the fountain-heads. . . For what has been said of the mystics applies above all to women, since it is they who have preserved the sense of the mystical in our earth to this day. — Maurice Maeterlinck.

In the Kingdom of Harmony there is no beginning and no end; just as the objectless and self-devouring fervor of the soul, all ignorant of its source, is nothing but itself, nothing but longing, yearning, tossing, pining — and dying out, i.e., dying without having assuaged itself in any "object"; thus dying without death, and therefore everlasting falling back upon itself. — Wagner's Artwork of the Future, 1849.

In a drama concerned so much with soul-events as this we have but little to do with Time and Space. We therefore find here no definite lapse of time indicated between Acts I and II. From subsequent events it is evident that Isolde is resting after the voyage prior to the celebration of the nuptials with King Marke. Since that memorable landing she and Tristan have been apart; but Isolde has never departed from her resolve to win Tristan from the Day and "take him hence to the Night" of the inner life, and so she seizes the opportunity for a meeting when the royal party are absent on a night hunt.

The scene is in the garden outside her apartments and the Act is divided into three parts: Isolde's expectancy; the great scene between Isolde and Tristan; and the surprise by Marke and his hunting-party.

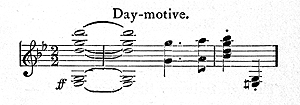

The wonderful music of the first scene has been sufficiently described by Mr. Neresheimer in the August number of Theosophy, and therefore I will only call attention to the theme which breaks like a shrill and menacing cry on the shimmering silence of the summer evening. It is the motive of that terrible Day, from the torment and illusion of which the soul is yearning to flee.

But the soul that aspires to the higher life always has an enemy in the shape of its own lower nature, which arises at the portal and seeks to bar its progress. In Tristan's case this foe is Melot, a fellow-knight, who pretends to be his friend but is really jealous of him. While Isolde is waiting for Tristan, Braugaene warns her of this danger: "Thinkest thou," she urges, "because thou art blind the world has no eyes for thee?" She knows that Isolde is not of this world and does not see with its eyes, and so she tries to show her that Melot planned the night-hunt, whose faint horn-echoes can be heard, in order to entrap them unawares.

But Isolde, with wider vision, knows that this seeming enemy will prove a friend by hastening their final release. She hints to Braugaene of a greater power behind these works of friend and foe which moulds them all in the end for good:

Frau Minne, knew'st thou not?

Of her Magic saw'st not the sign?

The Queen with heart

Of matchless height,

Who brings by Will

The worlds to light;

Life and Death

Are left in her sway

To be woven of sweetness and woe;

While to love she lets hatred grow.

This "Frau Minne" is the great Love-Spirit of the Universe herself, the Universal Mother, in whom now Isolde declares her absolute faith and trust.

The signal for Tristan is to be the extinguishing of a torch, the symbol of "daylight's glare," which stands at the gate; and, telling Braugaene to depart and keep watch, Isolde puts it out with the words:

Frau Minne bids

Me make it Night

. . . . . . . .

The torch —

Though to it my life were bound, —

Let laughter,

As I slake it,

be the Sound!

Have we not heard of this "laughter" before in the Ring of the Nibelung associated with "love" and "death" when Brynhild greets Siegfried on her awaking?

Tristan quickly answers to the signal and the first words of greeting tell us — if we need the assurance — that they have not met since Day tore them asunder on the ship: "Dare I to dream it? . . . Is it no trick? Is it no tale?" But the first joyful transports over they speedily soar into higher realms of consciousness where their speech is that of the Mysteries:

Past the search

Of sense uplifted!

Light beyond

The reach of leaven!

Flight from earth

To farthest heaven.Forever only one

Till World and Will be done!

And then together they review the mistakes of the past. Isolde tells Tristan it was "the Day that lied in him" when he came to Erin to woo her for Marke and "doom his true-love to death." For death indeed it would be to her to be chained to the Day of Marke; and Tristan truly answers: "In the Day's be-dazzling shine, how were Isolde mine? Then he goes on to tell of the inner vision which had come to him in the midst of earthly fame:

What, in the chaste night, there,

Lay waiting deeply hidden;

What without knowledge or thought,

In the darkness my heart had conceived;

A picture that my eyes

Had never dared to behold,

Struck by the day's bright beams

Lay glittering in my sight.

It was "Day's false glare," as Isolde shows him, which blinded his inner vision then; but now he is being gently led by her, step by step, as "head" is led by "heart." It is the central scene of an allegory of initiation where the innermost mysteries are being gradually unfolded to the soul's gaze. The supreme moment is close at hand as Tristan proclaims that,

He who, loving, beholds

Death's Night,

To whom she trusts her secret deep —

For him Day's falsehoods, fame and honour,

Power and gain, so radiantly fair,

Are woven in vain like the sunbeam's dust.

Amid the Day's vain dreams

One only longing remains,

The yearning for silent Night.

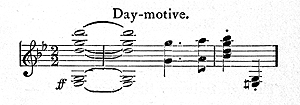

A motive is now heard which seems to be expressive of the throwing off of all earthly desire, and the supreme bliss of Union with the All. This motive appears again with magnificent effect later in this Act and also at the end of the drama, in Isolde's transfiguration, to her last words: "In the World's yet one all swallowing Soul — to drown — go down — to nameless Night — last delight!" Its entry, therefore, at this point, should be noted:

Immediately there follows the first great climax with the perception of this truth — the first glimpse of the Unity of Being: —

Deep in our hearts the Sun is hid,

The stars of Joy light laughing up.

And I myself — am now the World!

As they sink back in deep absorption of this wondrous vision, Braugaene, hidden in her watch-tower, is heard warning them that "Night is now at speed." Isolde hears her, and gently whispers "List beloved," while a motive of great peace and restfulness appears.

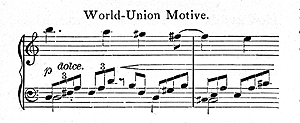

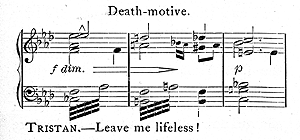

It is derived from the motive of Death-defiance and is followed by a new form of the Death-motive to Tristan's answer, "Leave me lifeless!"

Finding Tristan is still firm in his death-resolve, Isolde leads him yet a step further. He has felt his oneness with all humanity and now he must understand the mystery of his own new birth, as something higher than his present self, through this mystical love-death.

"But our love," she asks, "is not its name Tristan and Isolde?" Did Tristan go alone to death that bond would be disturbed. So the second truth flashes on him: they will "die to live, to love, ever united" in a "nameless" (namenlos) state in which they will be "surrendered wholly each to each."

As Tristan makes this further advance the motive of the Death-song appears in which Isolde presently joins:

Again comes the warning voice, "Already Night gives way to Day"; but the soul is now past all fear of illusion, and with imposing mien Isolde's fiat goes forth: "Henceforth ever let Night protect us." The second climax is reached and together they burst forth with the song:

O endless Night, blissful Night,

Fervently longed-for Death-in-Love.

Thou, Isolde — Tristan, I,

No more Tristan, nor Isolde;

Nameless, ever undivided.

And the music! How can it be described? Once more the theme of the Death-song appears combined with a soaring theme of ecstasy, and the whole is worked up with ever more superhuman power until the supreme height is reached with the re-entry of the all embracing World-Union motive to the words, "Ceaseless, whole, and single soul."

On the last word of the song a shriek is heard from Braugaene and Kurvenal rushes in with drawn sword, crying: "Save thyself, Tristan." He is followed by Marke, Melot and others. How Tristan now regards them is seen by his ejaculation: "The barren Day, for the last time!" Morning is dawning as the echoes of the great song of bliss die away and Melot triumphantly asks Marke if he has not accused Tristan truly. Now comes the greatest pain for Tristan and he sees how deep a wrong he did to Marke in winning Isolde for him. The good and noble-hearted King is torn with grief at the faithlessness of his friend, which he cannot understand: "Oh, where shall truth be found, now Tristan is untrue?" And as, in broken voice, he tells how, left widowed and childless, he loved Tristan so that never more he wished to wed, the unhappy knight sinks his head in greater and greater grief. Marke's words about the princess whom Tristan would fain woo for him are significant: (1)

Her, my desire ne'er dared approach,

Before whom passion awestruck sank.

Who, so noble, fair and holy,

Bathed my soul in hallowed calm . . .

But what comes out most strongly is the pathos of his inability to fathom "the undiscovered, dark and dread mysterious cause" of it all. Upright and noble, this royal figure is yet but the expression of the best that the outer world of Day can offer. The Mysteries are a closed book to him. All this finds a concrete expression in the Clarke-motive:

How thoroughly everyone who has entered at all into the realm of Occultism can sympathize both with Marke and Tristan! How well they know the truth of Tristan's words as he raises his eyes with sympathy to his heartbroken friend:

O king, in truth I cannot tell thee, —

And none there is that e'er can give thee answer.

But the music tells us, for it sounds the first Tristan-Isolde motive, which passes into the peaceful Slumber-motive as Tristan turns to Isolde and asks her if she will now follow him to the land where the sun never shines. Isolde replies:

When Tristan falsely wooed

Isolde followed him then . . .

Thou takest me now to thine own

To show me thy heritage;

How should I shun the land

That encircles all the world?

The World-Union motive sounds again as Tristan bends down and kisses her softly on the forehead. Melot starts forward in fury and Tristan, drawing his sword, reproaches Melot for his treachery, and then attacks him. As Melot points his sword at him, Tristan lets his own guard fall and sinks wounded into his faithful Kurvenal's arms, while Marke holds Melot back from completing his fell work.

Thus the second act closes with a deed on Tristan's part which shows too great an eagerness to flee from the results of his mistakes ere he has worked them out. Regardless of what Isolde has just taught him, he has invited death at Melot's hands instead of fully facing his responsibilities and trusting to the Law to appoint the time when "Tristan and Isolde" shall be released from Day and given for Aye to the Night. And in the third Act we shall see how Isolde has still to sojourn in the world of Appearances while Tristan passes through a period of suffering and atonement.

(To be continued.)

FOOTNOTE:

1. These words of Marke's are clear evidence that Isolde is still to him an object of distant veneration, nor is there a word in his speech of rebuke to her. I accentuate this point here and elsewhere because it is commonly stated by critics that Isolde is already wedded to Marke. Only those who have studied all the versions can realize how Wagner has purified the story from the objectionable and unnecessary incidents introduced by other poets, and has brought out the true occult meaning of the legend. (return to text)