X. — The Classic Period Continued. — The Nineteenth Dynasty. — King Sethi. — Rameses the Great.

The Eighteenth Dynasty had failed to maintain its authority over the tributary nations of Asia, and even over Northern Egypt. Queen Neten-Mut survived her husband Horemhebi several years, and her symbolical representation, a sphinx or cherub, which was sculptured on a monument, indicates that she continued in possession of the royal dignity.

There followed a contention over the succession. The throne of Lower Egypt was occupied by Ra-en-ti, and now the dominion of Upper Egypt was seized by Rameses I. There are diverse accounts with regard to the lineage of this founder of the Nineteenth Dynasty. He himself assumed to be a descendant of Amunoph I. and Queen Nefert-ari-Aahmes, but there exists good reason for supposing him to have actually belonged to Lower Egypt and to the race of the exiled monarchs. His physiognomy was decidedly Grecian, and his immediate successors differed distinctly in features from the Egyptian kings. They also recognized the Asiatic divinity Sutekh among the god's whom they worshipped, a fact that made them unacceptable to the priesthood of Thebes, which had now become a powerful hierarchy in Egypt.

The Khitan dominion meanwhile came into power at the north of Syria, and included all the neighboring nations from Kurdistan to the Archipelago as subjects and allies. At times his influence extended to the hordes of Egypt itself, and the Seventeenth Dynasty is described by Mariette Bey as "an offshoot of the Khitans, who inhabited the plains near the Taurus mountains, and were worshippers of Sutekh." The Khalu or Phoenicians, the Rutenu or Palestinians, and the Amairu or Amorites were subject to them. Sapuriri or Sapor was now the Overlord and king of this Semitic-Turanian people.

Rameses had first the task to make himself supreme in both realms of Egypt. He then led an expedition against the Khitans, to expel them from Palestine and Syria. It resulted in a treaty of alliance, offensive and defensive, between the two monarchs. Each pledged himself to keep within the limits of his own possessions, and to abstain from interfering with the other.

The reign of Rameses was short, probably not exceeding six years. He was succeeded by his son, Sethi I., also designated by the royal and official titles of Ma-men-Ra and Mene-Ptah. As the name of this monarch was similar to that of the divinity who was proscribed in the later Egyptian worship as the Evil Potency and slayer of Osiris, it was afterward generally erased from the sculptures, and that of Asiri or Osirei substituted. He married Tuaa, the grand-daughter of Amunoph III., or, as some say, of Khuenaten. His reign was characterized by great activity, both as a warrior and builder. Indeed, Baron Bunsen considered him to have been the famous king Sesostris, whose conquests were distinguished above those of other princes. Whilst, however, some identify this sovereign with one of the Osirtasens of the illustrious Twelfth Dynasty, the general judgment has decided that Rameses II. was the person so distinguished.

The Shasu tribes and the princes of Khanaan and Syria had formed leagues to establish their independence. Manthanar, the new king of the Khitans, it was affirmed, had also repudiated the treaty which had been made with Rameses. The throne of Sethi stood as on a mine of dynamite. Distrust at home and hostility elsewhere menaced him. He was, however, prompt in action. In the first year of his reign he assembled his troops at the fortress of Khetam or Etham, near the eastern boundary of Egypt. Thence he marched to the migdol or high tower, and on to Buto or Baal-Zapuna. He then traversed the territory of the Shasu-Idumseans without resistance, halting at Ribatha or Rehoboth in the "South country of Palestine." The confederated tribes, however, had made a stand at the fortress of Khanaana in the "land of the Zahi," or Phoenicians. The battle which ensued resulted in a complete victory for the Egyptians.

Sethi next turned his arms against the Phoenicians themselves and annihilated their forces at Jamnia. He followed up the campaign against the kings of the Ruthens or Canaanites, and afterward marched against "Kadesh in the territory of the Amorites." (1)

The Khitan frontier was now open, and he led his troops into that country. The war was continued for several years, after which a new treaty was formed.

Sethi returned home from his first campaign with a large number of prisoners and a rich booty. He took the country of the Lebanon on his way. The inhabitants had made no resistance, and he now employed them to cut down cedar trees for ships and for masts to set up at the Egyptian temples.

He was met near Khetam, at the frontier of Egypt, where he had set out, by a large multitude, the priests and chief men of Egypt. "They had come," we are told, "that they might welcome the Divine Benefactor on his return from the land of Ruthen, accompanied by a booty immensely rich — such as had never happened since the time of the Sun-God Ra." He had "quenched his wrath on nine foreign nations, and the Sun-God himself had established his boundaries."

The occasion was significant. The priests and nobles had need to be on good terms with a king, whose power was so demonstrated, and Sethi had good reason to desire the friendship of a sacerdotal order that might refuse funeral rites at his death, and uproot his posterity. Accordingly he enriched the temple of Amun-Ra with his booty and the priests in return chanted hymns of praise to "His Holiness."

"He had smitten the wandering peoples, and struck down the Menti; and had placed his boundaries at the beginning of the world and at the utmost borders of the river-land of Naharaina, and the region which the Great Sea encircles."

In the temple of Redesieh which Sethi built in the desert near the gold mines on the way from Koptos to the Red Sea another record was made. It describes him as having conquered the peoples of Singara, Kadesh, Megiddo, Idumasa, and several others which are not identified. In short, he not only included the countries of Palestine, Idumaea and Syria in these conquests, but they embraced the entire region from Assyria and Armenia to Cappadocia, together with Cyprus and other islands of the Mediterranean. Mr. Sayce, however, qualifies these reports. "It is difficult to determine the extent of Sethi's successes," he remarks, "since like many other Egyptian kings he has at Karnak usurped the inscriptions and victories of one of his predecessors, Thothmes III., without taking the trouble to draw up a list of his own."

The Thuheni of Libya had taken advantage of his absence from Egypt to invade the Lowlands of the north. They were fair of complexion and probably akin to the Pelasgians of Europe. Thothmes had subjugated them, but they had since refused to pay tribute. Sethi and the prince Rameses led an expedition against them and succeeded in reducing them to subjection. The prince, also conducted a campaign against the Amu tribes east of the Nile with success.

Sethi anticipated changed conditions for Egypt, and began the construction of a long wall on the northern frontier. It began at Avaris or Pelusium, and extended across the isthmus to Pi-thom or Heropolis, where the lagoons began, which are connected with the upper end of the Red Sea.

Sethi did not neglect the welfare of his subjects. He opened a canal from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea, for commerce, and it made the land of Goshen fertile. He was also diligent in procuring ample supplies of water, and caused artesian wells to be bored in the desert. In the poetic speech of the time, "he spoke and the waters gushed forth." As every temple had its tank or lake, he placed a little shrine at each of the wells to consecrate the spot and assure their maintenance. "Thus," says an inscription, "thus did King Sethi do a good work, the beneficent dispenser of water, who prolongs life to his people; he is for every one a father and mother."

Following the example of several of his predecessors, Sethi early contemplated the confirming of his regal authority by associating his son with himself in the government. The great historic inscription in the temple of Abydos describes the coronation of the prince.

"The Lord of all — he nurtured me and brought me up. I was a little boy before I attained the government; it was then that he gave the country into my hands. I was yet in the womb of my mother when the grandees saluted me with veneration. I was solemnly inducted as the Eldest Son into the dignity of the throne on the chair of the earth-god Seb. Then I gave my orders as chief."

"My father presented me publicly to the people; I was a boy in his lap, and he spoke thus: 'I will have him crowned as king, for I desire to behold his excellence while I am myself alive.' [Then came] the officials of the court to place the double crown upon my head, and my father spoke: 'Place the regal circlet on his brow.' [He then invoked for him a worthy career.] Still he left me in the house of the women and of the royal concubines, after the manner of the princesses, and the young dames of the palace. He chose for me [guards] from among the [maidens], who wore a harness of leather."

It could not have been for many years that the prince was left with his little troop of Amazons. It was the purpose of Sethi from the first, both from affection and from policy, to place his son actually in power. This is fully set forth in another inscription.

"Thou (Rameses) wast a lord (adon) of this land, and whilst thou wast still in the egg thou actedst wisely. What thou saidst in thy childhood took place for the welfare of the land. When thou wast a boy with a youth's locks of hair, no monuments saw the light without thy command, no business was transacted without thy knowledge. When thou wast a youth and countedst ten full years, thou wast raised to be a Rohir or ruler in this land. From thy hands all buildings proceeded, and the laying of their foundation-stones was performed."

Henceforth Egypt had a legitimate king. Sethi governed and the voice of Rameses Mei-Amun gave full validity to his acts. The two made war together, and under their administrations another building period began in Egypt. Thebes, from being the chief city of a province or minor realm, had become the capital of the whole kingdom, and attained to the height of its power and magnificence.

Wilkinson describes this period as "the Augustan Age of Egypt, in which the arts attained the highest degree of excellence of which they were capable." He adds, however, the dark premonition, that as in other countries their culmination-point is sometimes marked by certain indications of their approaching decadence, so a little mannerism and elongated proportion began to be perceptible amidst the beauties of the period.

The buildings which were begun in this reign were masterpieces, never equalled by later structures. It had always been the endeavor of the sovereigns of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Dynasties having Thebes for their metropolis that it should rival in splendor the earlier capitals, Memphis and Heliopolis. Sethi was generous to the sanctuaries in different cities of Egypt, but his most famous memorials were the temple of Osiris at Abydos, the "House of Sethi" at Gurnah, and the Hall of Columns, in the temple of Amun-Ra. at Thebes. This latter structure was a hundred and seventy by three hundred and thirty feet in area, and its stone roof was supported by one hundred and thirty-four columns, the tallest of which were seventy-five feet high and twelve feet in diameter. Several of them have fallen at different periods; nine of them in the summer of 1899. The walls are covered with sculptures and inscriptions; those on the north side setting forth the conquests of Sethi and those on the south the exploits of Rameses II.

The splendor of these buildings consisted in the profusion and beauty of the sculptures, even to the hieroglyphic characters. Mr. Samuel Sharpe has explained the general use of these symbols on the monuments by the supposition that papyrus had not then been used for writing. Later discoveries, however, have proved this to be an error. The tombs which have been opened of monarchs of earlier dynasties have been found to contain scrolls. Prof. Ebers, also, in his romance, "Uarda," setting forth occurrences of the reign of Rameses II., describes the "House" or Temple of Sethi at Karnak, on the western side of the Nile, a school of learning only inferior to the temple of Hormakhu at Heliopolis. Here were instructed priests, physicians, judges, mathematicians, astronomers, grammarians, and other learned men. (2) The graduates received the degree of grammateus, scribe or doctor, and were at liberty afterward, at the public expense, to prosecute scientific or philosophic investigation as their taste impelled them.

There was also a School of Art, with regulations of a similar character, and likewise an elementary department at which every son of a free citizen might attend.

The Memnonium, or, more correctly, Me-amunei, was a temple begun by Sethi on the western bank of the Nile in honor of his father Rameses I. The pillars were modeled to represent bundles of papyrus-reeds. The inscriptions in it have evidently been changed to meet religious prejudice. The king is named Osiri, and Osiri-Seti — but the last name is not that of Typhon. The building was dedicated to the deceased monarch Rameses I. and to the gods of the Underworld, Osiris and Hathor, (3) as also to Amun-Ra and his group of divinities. The death of Sethi took place while the temple was in process of construction; Rameses II. finished it and directed the inscriptions.

"King Rameses II. executed this work as his monument to his father, Amun-Ra, the king of the gods, the lord of heaven, the ruler of Ta-Ape (Thebes); and finished the House of his father King Meneptah-Sethi. For he (Sethi) died and entered the realm of heaven, and he united himself with the Sun-god in heaven, while this House was being built. The gates showed a vacant place, and all the walls of stone and brick were yet to be upreared; all the work in it of writing or painting was unfinished."

The temples of Abydos are interesting to us as aiding to unravel the tangled web of Egyptian history. Here, it was declared, Osiris had been buried, and hence Nifur, the necropolis of that city, was a favorite burial-ground, especially after the Twelfth Dynasty. Sethi began the construction of two shrines, a larger and a smaller, as a memorial to' his ancestors. They were afterward finished by Rameses in most magnificent style, and decorated profusely with sculptures and inscriptions. The names of both monarchs, the father and son, were placed in each. In a smaller temple was set the famous Tablet of Abydos, which they had dedicated to the memory of the predecessors whom they recognized as genuine and legitimate kings of Egypt. The list begins with Mena and extends to Rameses Mei-Amun, omitting the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, Fifteenth, Sixteenth and Seventeenth Dynasties.

M. Mariette has discovered another Tablet in the larger temple, which is described as being more complete. Amelineau has also been engaged several years in explorations, and some of his discoveries throw new light upon Egyptian history and archaeology.

Rameses II. was now sole king of Egypt. He had chosen the city of Tanis or Zar for a royal residence. It had a commanding strategic position, and had been the starting-place of former kings upon their military expeditions. The Arabian tribes, the Idumseans and Amalakites, at that time held the country immediately beyond. Its Hyksos kings had fortified the city and built temples there for the worship of Baal-Sutekh. It had an extensive commerce by caravans from, Arabia, and its harbor, like that of Alexandria in Grecian and Roman times, was filled with shipping, bringing and carrying merchandise. Here the young monarch erected temples to the guardian divinities of the realms of Egypt, Amun, Ptah and Hormakhu, including with them the tutelary of the Semitic nomes, Baal-Sutekh. The new temple-city, called Pi-Ramesu, was afterward supplied abundantly with statues, obelisks, memorial-stones and other religious paraphernalia. The court was established here, with its chief officials, Khartumim or soldier-priests, (4) and other functionaries.

In the first year of his reign Rameses made a voyage to Thebes to celebrate the Feast of the Advent of Amun-Ra to Egypt. It began on the thirteenth of September and lasted twenty-six days. The king at the conclusion "returned from the capital of the South," says the inscription of Abydos. "An order was given for the journey down the stream to the stronghold of the City of Rameses the Victorious."

His next progress was to visit the tomb and temple of Sethi at Abydos. A second voyage was made accordingly, and he entered Nifur, the necropolis, by the canal from the Nile. He found the structure unfinished, and the tombs of the earlier kings were dilapidated from the very foundations. (5) Rameses immediately assembled the princes, the friends of the dynasty, chief men and architects. (6) "When they had come, their noses touched the ground, their feet lay on the ground for joy; they prostrated themselves on the ground, and with their hands they prayed to the king."

Rameses addressed them with upbraiding upon the condition of the temples, tombs and monuments. These required labor, he declared. Sons had not renewed the memorials of their parents. (7)

"The most beautiful thing to behold, the best thing to hear, is a child with a thankful breast, whose heart beats for his father; wherefore," the king adds, "my heart urges me to do what is good for Meneptah." He then recounted the kindness and honor that had been bestowed upon him by Sethi. He had been set apart from his birth for the royal dignity, and at ten years old had been crowned and invested with regal authority. "I will not neglect his tomb, as children are accustomed to do," he declared. "Beautifully shall the most splendid memorial be made at once. Let it be inscribed with my name and the name of my father."

Orders were given for the repair of the tombs and for the building of the "most holy place" of his father and the temple. Statues were carved and the revenues for the maintenance of his worship were doubled. What had been already done in honor of Sethi at Thebes, Memphis and Heliopolis was repeated at Abydos. Priests of the vessel of holy water with which to sprinkle the ground were appointed, and a prophet to take charge of the shrine. The inscription recapitulates a large catalogue of the services that were provided, and Rameses concludes with an invocation.

"Awake, raise thy face to heaven, behold the sun, my father, — Meneptah, —

Thou art like God . . . .

Thou hast entered into the realm of heaven; thou accompaniest the Sun-God Ra.

Thou art united with the stars and the moon,

Thou restest in the deep like those who dwell in it with Un-Nefer,

The Eternal One.

Thy hands move the god Turn in heaven and on earth,

Like the planets and the fixed stars.

Thou remainest in the forepart of the bark of millions. (8)

When the sun rises in the tabernacle of heaven

Thine eyes behold his glory.

When Turn [the sun at evening] goes to rest on the earth

Thou art in his train.

Thou enterest the secret house before his lord.

Thy foot wanders in the deep.

Thou abidest in the company of the gods of the Underworld."

Rameses concludes the inscription by imploring his father to ask of the gods Ra and Un-Nefer (Osiris) to grant him a long term of life — "many thirty years' feasts" — and promises that in such case Sethi will be honored by a good son who remembers his father.

The inscription gives the reply of the deceased "Osiris-King," Sethi, assuring Rameses of his compliance.

There is a whisper that the priests of Thebes had refused a place to Sethi at the necropolis of that city. This may have been the cause of the unsolved question in regard to his two sepulchres.

The tomb of Sethi, in the valley of the Kings, is described by Mr. Samuel Sharpe as the most beautiful of any in Egypt. It eluded alike the curiosity of the explorer and the cupidity of the Arab, till it was discovered by Belzoni. He found the paintings and other works of art with as fresh an appearance as when the tomb was first closed. The entrance was in the side of the hill. There was a dark stairway of twenty-nine feet, then a descending passage of eighteen feet, then a second stairway of twenty-five feet and a second passage of twenty-nine feet. This constituted the pathway to the first grand hall. This was a room of about twenty-nine feet square, and its roof was supported by four square pillars. A little way on was a second hall of similar dimensions; then a passage and a smaller apartment, beyond which was a third hall of twenty-seven feet square. This opened into a small room in which was the royal sarcophagus. It was of alabaster, and around it were hundreds of little wooden images in the form of mummies. (9)

The walls of these caverns were covered with sculptures painted and highly finished, and with inscriptions setting forth the fortunes of the disembodied soul. The roof of the "Golden Chamber" is covered with pictures having special significance in regard to the stars and their influence. In a little room at one side is an inscription representing a destruction of the corrupt place of human beings. (Compare Genesis vi., vii.) Upon the cover of the sarcophagus is a representation of the Great Serpent of Time borne by a long procession of nude figures. The Serpent was conspicuous in a variety of characters in all the Egyptian temples. In the tomb of Amunoph III. is a procession of twelve snakes, each on two legs, and convoluted like the other so as to produce the classic fret-molding.

The perfectness of these works far exceeds the later productions of the reign of Rameses. This was probably because they had been begun by artists employed by Sethi himself. The scenes which are depicted indicate a change of some kind in religious sentiment, and exhibit a conforming to the worships of western Asia. There were depicted in a garden the river which separated the dead from the living, the bridge of life and its keepers, also the tombs of the dead with sentinels at their doors. The god Um-Nefer or Osiris sits upon a lofty throne, holding the sceptre of the two realms, but wearing the crown of Upper Egypt alone. Human beings are climbing the steps, and before him are the scales in which their conduct during life is to be weighed. Beneath are condemned ones at work like miners in the mines.

Funeral ceremonies and also the Initiatory Rites at this period consisted in part of the Scene of Judgment by which the condition of souls was determined. It is easy to see that the descriptions given in the AEneid of Virgil and other classic works, such as those of the river Styx, and the souls of the dead coming thither to cross from this world into Hades for judgment, the Kharon or ferryman, the Eumenides and other scenes, were taken from the later rites and mythology of Egypt.

This tomb was not completed till the later years of the reign of Rameses, and there had been significant changes made in the inscriptions, indicative of modifications in the religious institutions. Rameses was a statesman rather than a priest, and he gave a license to foreign worship that the sacerdotal leaders did not approve.

It became necessary for him at an early period to trust his fortunes to the arbitration of war. Manthanar, the king of the Khitans, refused to abide by the treaties which had been made with Sethi and Rameses I., and the tributary princes of Syria, Phoenicia and Palestine had again thrown off the yoke of Egypt. The Grand Monarch of the Nineteenth Dynasty was not the man to falter in exigencies or to hesitate about the employing of agencies that were at his command. Heretofore the native peasantry and agricultural population of Egypt had been regarded as exempt from military service. Soldiers were needed and Rameses conscripted them for the war in Asia. He set out upon his first expedition in the second year of his reign. The accounts of this compaign are meagre. He states that he conquered everything in his way, (10) and set up memorial pillars at various places, setting forth his triumphs. Where he was not opposed he erected monuments in honor of the tutelary goddess Astarte or Anait. He penetrated as far as Kadesh on the Orontes, when truce was agreed upon and he returned to Egypt.

The next year he directed his attention to the financial resources of his kingdom. He held a council of the princes at Memphis, and obtained pledges of their support. "As soon as they had been brought before the divine benefactor (euergetes) they lifted up their hands to praise his name and to pray. And the king described to them the condition of this land [the gold-bearing land of Akita in Nubia], in order to take their advice upon it, with a view to the boring of wells on the road." A royal Scribe was accordingly dispatched to the region with the necessary authority. Water was obtained in abundance, forming lagoons twelve cubits deep, in which fishermen sailed their boats. "And the inhabitants of Akita made joyful music" and offered thanks to the king "Rameses Mei-amun the Conqueror."

Again the dark cloud of war loomed above the horizon. The king of the Khitans had formed alliances with the sovereigns of neighboring countries, not only with the princes of Syria, Phoenicia, Palestine and Arabia, and with the kings and peoples of Arvad or Aradus, Khalibu or Aleppo, Naharaina or Mesopotamia, Kazanadana or Gauzanitis, Karkhemosh, Kittim, Dardania, Mysia, Mseonia or Karia, Lycia, Ilion — all the peoples from the uttermost ends of the sea to the people of the Khita. "He left no people on his road without bringing them with him. Their number was endless, and they covered the mountains and valleys. He had not left silver or gold with his people; he took away all their goods and possessions to give to the people who accompanied him to the war."

He again challenged the king of Egypt. Rameses collected his forces, actually depicting the fields and workshops to swell their number. Among his auxiliaries were the Sardonians of Kolkhis. This campaign is depicted in fulsome language in the inscriptions on the walls of the temples, and the prowess of the king is described as sublime, especially in the heroic poem of Pen-ta-ur, the Homer of the Nile. (11)

Rameses set out on his second expedition, leaving the fortress of Khetam on the ninth day of the month Payni, in the fifth year of his reign. He was accompanied by six of his sons. The place of destination was the city of Ka-desh, on the river Orontes. His route was by the Path of the Desert, "the way of the Philistines," and the usual military road to Palestine. A month later he arrived at the city of Rarneses-Ma-Amun, in Zahi or Philistia. At Sabbatanu (Sabbath-town) two Arab spies, pretending to be deserters and loyal to Egypt, met the advance guard, with the story that the king of the Khitans had retreated to the land of Khalibu, north of Daphne, in fear of the Egyptians. Immediately the various legions of Amun, Phra, Ptah and Sutekh marched to the south of Kadesh, where they were attacked by an ambush while unprepared and put to rout.

Rameses himself was on the western side of the river. "Then the king arose like his father, Menthu, and grasped his weapons and put on his armor like Baal in his time. He rushed into the midst of the hostile hosts of Khita all alone; no other was with him. He found himself surrounded by twenty-five hundred pairs of horses, and his retreat was cut off by the bravest heroes (mohars) of the king of the miserable Khitans."

"And not one of my princes, not one of my captains of the war-cars, not one of my chief men, not one of my knights was there. My warriors and my chariots had abandoned me, not one of them was there to take part in the battle."

When Mena, the driver of the royal car, beheld the pairs of horses around him, he was filled with alarm and terror. He implored the king to save himself, and thus to protect his people. The intrepid monarch replied to him encouragingly and then charged as with desperation upon the foe. "He rushed into the midst of the hostile hosts of the king of Khita, and the much people with him. And Pharaoh, like the god Sutekh, the glorious one, cast them down and slew them."

Evidently the very numbers of the enemy by being crowded upon one another made them powerless before him. "And I," says Rameses, "I, the king, flung them down head over heels, one after the other, into the water of the Aranta."

When he charged upon them the sixth time he says: "Then was I like to Baal behind them in his time, when he has strength, I killed them, none escaped."

When the evening had come and the battle was over, his army, the princes and others, came from the camp and beheld the carnage. There lay the last combatants of the Khitans, and the sons and brothers of their king, weltering in their blood. Rameses was severe in his reproaches. "Such servants are worthless," said he; "forsaken by you, my life was in peril; you breathed tranquilly and I was alone. Will any one obey him who leaves me in the lurch, when I am alone without my followers, and no one comes to me to reach out his hand? . . . My pair of horses, it was they that found me, to strengthen my hand. I will have their fodder given to them in my presence, when I am dwelling in the palace, because I have found them in the midst of hostile hosts, together with Mena, the captain of the horsemen, out of the band of the trusted servants of the palace who stayed near me."

The battle was renewed the next day, and was little less than a massacre. "He killed all the kings of all the people who were allies of the King of Khita, together with his princes and senators, his warriors and horses."

One of the scenes represented in the sculptures at the Hall of Columns at Thebes exhibits the king standing in his car pressing forward into the thickest of the fight. He drives the enemy over a bridge, one of the earliest on record, and one of the opposing kings, vainly resisting the onslaught, is drowned in the Arunata. The city is stormed and prisoners taken.

The Khitan monarch, it is recorded, asked a truce, and a council of officers implored Rameses to grant the request. Evidently the victory was not decisive, despite the testimony of the hieroglyphics.

"Then the king returned in peace to the land of Egypt. All the countries feared his power as the lord of both worlds. All the people came at his word, and their kings prostrated themselves to pray before his countenance. The king came to the city of Rameses Mei-amun and there rested in his palace."

This, however, by no means terminated the hostilities. The Khitans had not really been conquered. They were able to continue the war. The kings of many cities refused to submit to Egypt. In the city of Tapuna or Daphne, in Mesopotamia, where Rameses had set up two of his statues, as master, the rulers and populace continued hostile. Finally he led an army into Naharaina and reduced them to subjection.

The inhabitants of Palestine were also restless. Finally, in the eighth year of his reign, he invaded the country, captured the principal fortified towns, "placing his name there," and made prisoners of the kings, senators and men able to bear arms. These were made to submit to indignities; they were beaten, their beards were plucked out, and they were afterward carried away captive into Egypt.

In the eleventh year Rameses made a campaign against Askalon. A long and fierce resistance was made, but the city was captured and sacked. Warlike expeditions were also undertaken against the negro tribes of the south and a multitude of prisoners was taken and reduced to slavery. These expeditions are fully depicted on the monuments: The "king's sons" leading forward the men before the god Amun-Ra, "to fill his house with them."

About this period there was another general migration of peoples, such as had occurred every few centuries with almost mathematical regularity. Warlike tribes moved southward and westward, supplanting or mingling with the former populations, and disturbing whatever equilibrium had before existed. This made a cessation of hostile relations between Khita and Egypt of vital importance. The two countries had wasted their energies in conflict which brought no permanent advantage to either. Manthanar, the king of the Khitans, having been assassinated, his brother Khitasar, who succeeded him, sent ambassadors to Egypt to negotiate a treaty. They brought with them engraved on a silver tablet the text of "a treaty of friendship and concord between the Great Prince of Egypt and the Great King of Khita." (12) The monarch introduces the proposed negotiation with a declaration of personal esteem. "I have striven for friendly relations between us," he says, "and it is my wish that the friendship and concord may be better than what has existed before, and never broken."

Upon the middle of the tablet and also on the front side of it was engraved the likeness of the god Sutekh, the Baal of Syria and Northern Egypt. The male and female gods of each country are also indicated as "witnesses of these words," and the denunciations added that whoever shall not observe the terms of the treaty will be given over with his family and servants to their vengeance. Unconditional and everlasting friendship is solemnly pledged, and the treaties which had been made between the former kings are renewed. Each king promised not to overstep the boundaries of the other, even if anything should be plundered. In cast an enemy invaded the dominions of either, and he made application to the other for help, the call would be answered with a sufficient military force. Fugitives from justice fleeing from one country to the other were to be put to death as criminals, and the servants of either king escaping into the territory of the other must be returned for punishment. But if any inhabitant of either country should migrate to the other, he also must be delivered up and sent back, but his misconduct should not be punished in any way; neither his house, his wife or children should be taken from him, nor should his mother be put to death, nor himself suffer any penalty in his eyes, on his mouth, or on the soles of his feet. In short, no crime or accusation was to be brought against him.

This treaty was ratified at the city of Rameses in the twenty-first year of the reign of the Egyptian king. It put an end to the contest that had so long existed for supreme power in the East, and left the two kings at liberty to deal with affairs at home, and with hostile or refractory princes in regions contiguous to their dominion. The amity thus established was more firmly cemented by closer relations. Thirteen years later the king of Khita visited Rameses in his capital, bringing his daughter, and she became the wife of the Egyptian monarch.

In conformity with the custom of ancient times, as is now the usage in Russia, still an Oriental country, the bride, being of a different race and worship, abjured them, and received a new name, Ma-Ua-Nefera. (13)

This alliance is mentioned in inscriptions in the temple of Pisam or Ibsarn-bul, in Nubia, bearing date in the thirty-fifth year of his reign. On the walls of that sanctuary was depicted a glowing description of the battle of Kadesh, the famous poem of Pentaur, and likewise a conversation between Rameses and the demiurgic god Ptah. This divinity belonging to Northern Egypt, and closely allied in his worship and personality to the Semitic divinities, as well as to Osiris and the Apis, was highly esteemed by the king, and Khamus, his favorite son and associate, was high priest in the Temple at Memphis.

The divinity relates the favors he has bestowed on the king, regal power, booty and numerous captives.

"The peoples of Khita are subjects of thy palace. I have put it in their hearts to serve thee. They approach thy person with humility, with their productions and booty in prisoners of their king; all their property is brought to thee. His eldest daughter stands forward at their head, to soften the heart of King Rameses II., a great and inconceivable wonder. She herself knows not the impression which her beauty has made on thy heart . . . Since the time of the traditions of the gods which are hidden in the houses of the rolls of writing history had nothing to report about the Khita people, except that they had one heart and one soul with Egypt."

The reply of Rameses is characteristic. He tells the god that he has enlarged the shrine at Memphis inside the Temenos or walled inclosure of the temple, that he has provided for the thirty years' jubilee festivals, and caused the whole world to admire the monuments which he has dedicated to him. ''With a hot iron," he adds, "I brand the foreign peoples of the whole earth with thy name. They belong to thee; thou hast created them."

The temple was literally a stone cut out of the mountain. Not without hands, however; but who the architect was, who planned the work, who performed it, all are alike unknown. Rameses filled Nubia with temples and towns commemorating his name, but this sanctuary dedicated to the Great Gods of Egypt, Ptah, Amun and Hormakhu and to Rameses-Meiamun himself, surpassed all in magnificence. It is richly embellished with sculptures, and its entrance on the East was guarded by four colossal figures, each with its eyes fixed on the rising sun.

Mr. Sayce makes the disparaging statement that Rameses cared more for the size and number of his buildings than for their careful construction and artistic finish. He describes the work as mostly "scamped," the walls ill-finished, the sculptures coarse and tasteless. But he adds, "Abu-Simbel is the noblest memorial left us by the barren walls and vain-glorious monuments of Rameses-Sesostris."

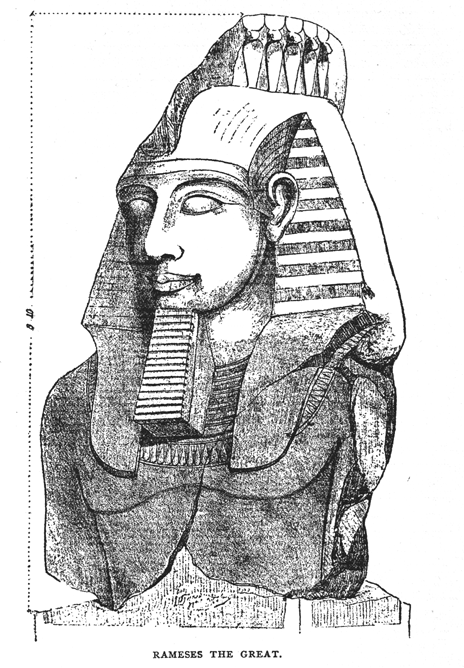

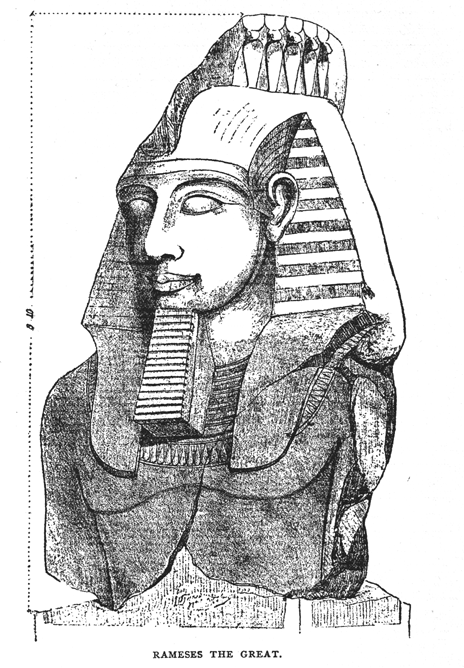

Rameses has sometimes been compared to Louis XIV. of France. A picture of him from the colossal figure at the temple in Abu Simhel gives him features resembling those of the first Napoleon, but there is ample reason to presume that the artist greatly disguised them. The sculptures representing Sethi and Rameses disclose a considerable resemblance. There is a strong resemblance in their features, and Rameses, though possessing less energy and strength of character than his father, had a more sensitive temperament, a wider range of taste and greater inclination toward peace. The latter thirty years of his reign were generally without war. He left the reputation of a great soldier and a warlike prince behind him; nevertheless, his tastes and career were more in analogy with those of the Grand Monarque. Like that king he had an ardent passion for building, and his Court was thronged with scholars and men of talent. His chief achievements were those of a reign of peace; the great wall of five hundred miles to protect the inhabitants of the valley of the Nile on the East from the incursions of the Amu and Shasu, the Suez Canal, the new cities, innumerable buildings, excavations, obelisks, statues of colossal dimension, and other works of art with which he adorned his dominions.

Nevertheless, the glory of Egypt was now waning, and a period of decline had already begun.

FOOTNOTES:

1. The name Kadesh, or K'D'S, signifies holy; hence, the sanctuary, "a holy city, or sacerdotal person. The place here mentioned is supposed to have been Ashtoreth Karnaim, the city of the two-horned goddess Astarte. (return to text)

2. The teachers, more than eight hundred in all, were priests; the general managers, three in number, were styled "prophets." The high priest was chief over them. Every student chose his preceptor, who became his philosophic guide, to whom he was bound through life, as a client or clansman to his chief or patron. (return to text)

3. Hathor, the "mother," was in another phase the same as Isis. She presided, like Persephone, over the world of the dead, as well as over love and marriage, for love and death are closely allied. (return to text)

4. The Egyptian term khar-tot signifies a soldier of high rank. The "magicians" of the Book of Exodus were khar-tots, and doubtless were of the sacerdotal order peculiar to the city of Rameses. They are described as on intimate terms with the king, and not as vulgar jugglers. (return to text)

5. The bricks employed in Egypt for building were made of mud, held together by chopped straw. Structures built of them could not last long without frequent renewing. (return to text)

6. Significantly, the priests are omitted. The Nineteenth Dynasty seems to have largely omitted them from employments of State. (return to text)

7. The rites to deceased parents and ancestors were anciently regarded as the most sacred office of filial piety. The souls in whose care these offices had been neglected were believed to suffer torment, and even sometimes to become evil demons, to obsess the delinquents. It was therefore imperative upon the head of a family, the patriarch, to marry and rear a son; to inter, cremate or entomb his parents; and at stated periods present funeral offerings. The mother of a son was thus the good genius of a family. The prophets and priests of the pyramids and tombs were set apart for the services, which at Abydos had been neglected. (return to text)

8. The Sun was supposed to ride every day in his boat through the sky, and so Sethi is described as his fellow-voyager. (return to text)

9. The term mummy is from the Persian term mum, signifying wax. It originally meant a body that had been inclosed in that material. (return to text)

10. He is called Sesostris by the historian, a Grecian form of the name "Sestura," by which Rameses was known. (return to text)

11. Pen-ta-ur was a hierogrammateus, or scribe, of the Temple of Kurna, where he had passed successfully through the different grades of Egyptian scholarship. He is described as "a jovial companion who, to the disgust of his old teacher, manifested a decided inclination for wine, women and song." He had the honor, in the seventh year of the reign of Rameses, to win the royal prize as the composer of this poem. We have a copy in a roll of papyrus, and its words also cover the whole surface of the walls in the temples of Abydos, El Uksor, Karnak and the Ramasseum of Abusimbel. It was translated by the Viscount de Rouge, and several versions have been published in English prose. Prof. Ebers has made Pentaur the hero of his Egyptian romance "Uarda," using the license of the novelist to make him the, successful lover of Bent-Anat, the king's daughter, and otherwise sadly confusing history. (return to text)

12. The adjective "great," which appears here and in other ancient documents, denotes that the monarch so designated was a "king of kings," lord over tributary kings and princes. Up to this time Egyptian records describe the kings of Khita, as they do other hostile princes, by such epithets as "leprous," "vile," "unclean;" but they ceased it from this time. (return to text)

13. The nuptials of Rameses, on this occasion, seem to have been literally described in the forty-fifth Psalm. "Kings' daughters were among thy honourable women; upon thy right hand stood the Queen in gold of Ophir. Hearken, O daughter, and consider; incline thine ear; forget also thy kindred and thy father's house; so will the king greatly desire thy beauty; for he is thy lord, and worship thou him." (return to text)